Chase Cofer remembers the day he experienced the first symptom.

It was a day like any other, with Chase and his sister spending time with their cousins. Chase hadn’t noticed anything was wrong – but his sister did. She pointed out that his arm had been in a fixed, bent position for the entire day.

When Chase tried to straighten his arm, he found that it would not move. His sister and cousins thought he was joking around.

When they realized that he really could not straighten his arm, everyone, as Chase puts it, “freaked out.” The problem was initially diagnosed as a pulled muscle. However, his family found out that something was seriously wrong when he finally made it to St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

“I was nine years old at the time,” says Chase. “By the time that I was 11 or12, my legs were locked up, my other arm was locked up, my fingers were locked up.”

Through recent genetic testing, Chase was found to have a mutation in sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase (SGPL1), which can result in nephrotic syndrome, ichthyosis, facultative adrenal insufficiency, immunodeficiency, and neurologic defects.

Overall, there are only 30 people worldwide identified with SGPL1 deficiency. The individuals, from 15 families, are from Pakistan, France, Spain, Canada, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, Austria, Israel, Serbia and the United States.

“I have a gene mutation,” Chase calmly states. “I’m the only person in the United States who has been reported with it.”

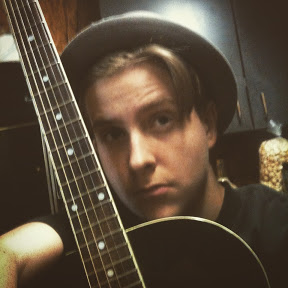

It has been a long road for Chase since that day 11 years ago. Occupational therapy helped straighten his arms. Surgery helped straighten his legs. But he was never able to get his fingers straight. Needing better home therapy for his fingers, he started playing guitar.

Chase has been playing guitar now for two years. “I am self-taught. I just love it. It’s great exercise.” But he also plays guitar because he loves music.

“Music just spreads joy. I’ve learned that I can put a lot of emotion into my songs using the guitar and spread any kind of joy. I like just about any kind of music. I play anything from blues to jazz to rock to rap. Anything you can think of, I will try and play it on guitar. I will try my best at it as I do with everything. I always give it my all.”

Chase recently transferred from Children’s Hospital to Chromalloy Dialysis Center for hemodialysis three times a week. “You know, being on dialysis takes up a lot of time, takes up a lot of your day. Still, I manage to play guitar two hours a day.”

Since picking up the guitar and composing his own music, Chase has posted 11 music videos on his YouTube channel, Milk Toof. See here for his first video posted in 2016 and another composition, This is Not a Test.

“I’ve written a few songs, but I can’t sing, so I need other people to sing them for me! Actually, my friend Chris and I’m trying to start my own band right now.”

Chase also wants to use his YouTube videos to tell his story. “I want to reach out and find people who have this disease, because there are still people out there who are trying to figure out what they have. They honestly don’t know. I was there once, and I was lucky to find Dr. Megan Cooper, who through a blood test was able to identify my disease. For almost 10 years, I was just guessing. I want others to find their Megan Cooper.”

“Chase is such a great person,” says Dr. Cooper, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics and Pathology and Immunology. “Through all of his challenging medical problems he has retained a positive spirit. “Whenever I see Chase, his first question is always How are you doing? The cause of Chase’s disease was only recently uncovered by genetic sequencing. We are hopeful that now that we understand the mechanism of his disease, we will one day be able to provide a targeted therapy for him and others with his condition.” Dr. Cooper is co-author of the recent publication titled Mutations in Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Lyase Cause Nephrosis with Ichthyosis and Adrenal Insufficiency in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Right now, Chase is learning to learn to walk again. “I’ve learned how to walk a few times in my life, but every time, something would happen. In 2016, I was walking probably 20 minutes in therapy, and then my kidneys started to fail.”

Although Chase admits that dialysis has been hard and that he looks forward to eventually getting a kidney transplant, he says that if he had the choice to be someone else, he wouldn’t. “You know, it’s been an honor for me to actually have this disease because I’ve been able to meet so many people and just spread positivity.”

Chase says not many people would view this disease in a positive light. But he does.

“I am someone who can truly handle this. And handle it well.”